When taken for its constituent parts—representation in situ, abstraction, metadata, and the culture that sits in-between—Cypriot-born Marina Xenofontos’ work beams into view. Looping between poetic conjectures, indexical evidence of process, and (your; my; her) short-term memory, the works play to a viewer’s longing for sentiments and associations that were never there, never personally experienced. This is Xenofontos’ craft: activating invisible nostalgia while moving between inhuman ontology and life-like storytelling, contending that reason is in retrospect. In anticipation of her Liste showcase, Marina and I discussed the methodical and material considerations which inform her practice. We spoke about retranslation—moving between digital/analog versions of the same avatar—and “reperformance”, Monobloc chairs, and about what possibilities exist, if any, towards the reclamation of abstraction.

Elizaveta Shneyderman (ES): There is a flow between digital and analog modes of working in your practice, as evidenced by an adolescent avatar Twice Upon a While (2018 – ongoing). The character is reanimated in virtual and physical form, lending it immortal status—and embedding the possibility of its infinite reanimation. How do you tackle the evolution between digital and analog representations, particularly when representation (and reperformance) is also constitutive of the work itself?

Marina Xenofontos (MX): When an image or material moves from digital to analogue, or the other way around, apart from the possibility of infinite reproduction—or as you put it, “reanimation”—the process generates small inaccuracies, slip-ups, and cracks, which eventually snowball and become more evident. It’s these types of errors that I routinely tap into. I started working on the avatar Twice Upon a While (2018 – ongoing) at Rjiksakademie. At first, this was for a video game about an ideologically befuddled teenager failing to complete her tasks. I’d been rendering the character digitally for a couple of months, and started to have the desire to see it in physical form. So, with a lot of help from the staff, I got it sliced, carved, and assembled using a CNC machine. A couple months later, at the Rijks Open Studios, I showed the first physical avatar– laying on the floor, grasping up to cover its eyes, seemingly in a state of desperation. Since then, I’ve carved several new versions of the work. The most recent iteration is the one I am presenting at Liste. Every time I carve a new version, it feeds back into my understanding of the virtual. At this point, all these versions have melded into one in my head– there isn’t an original anymore, they’re all glitching, mutating, and branching in and out of each other like a rhizome. Collectively, the work acts as a witness to memory that is disjointed and fragmentary, inescapably fallible, and as a testament to a confluence of errors.

ES: Speaking of errors, the defective Monobloc chair features prominently in your presentation. What role does the Monobloc play in your work, specifically in relation to its idiosyncratic status in Cyprus, as well as its colonial legacy?

MX: Monobloc chairs, known as the world’s “most common plastic chair”, are everywhere in Cyprus. We use them most frequently for any kind of outdoor celebration or ceremony, like weddings or around easter– basically any kind of event that requires quick set-up and fast take-down. I found the one I used in the Liste presentation in front of a taxi office called “New Faithful”, positioned on the pavement where the drivers hang out while waiting for bookings. “The Queen” type Monoblocs are made by Lordos Plastics, the largest plastics manufacturer in Cyprus, and because they were misprinted in the manufacturing process, they were usually sold to small businesses and factory workers at a discount. You’ll notice the blue one has white pigment marbled into it, probably because it was either the first or last chair on the production line between the two colors (they’re forged in single piece via injection moulding). And I think this uniqueness embedded through error is what drew me to them in the first place. These chairs are often used to order space. In school, we’d lay out Monoblocs in the courtyard whenever we had an announcement or an annual celebration, making what would usually be a really chaotic space organised and well arranged. Both universal and distinct, they’re a paradox; instances of unrepeatability within endless repetition.

ES: Children of builders, grandchild of miners (2020) is very meditative, and I can’t help but think that much of your work overall is composed of these dreamlike, sonorous compositions—allegorically embedded, materially dense. I wonder if that in part has to do with your interest in metadata. Can you speak more to this?

MX: The title of the work is biographical in a sense, my father worked in construction all his life and my grandfather in the Amiantos asbestos mines. It is also universal in the way that it traces a broader shift in labor. A lot of my work rests on these kinds of details, stories, anecdotes, or histories, which could all be placed under the umbrella of “metadata”. They usually come in the form of vestiges—either of a political event or change—buried and abstracted in a place you’d usually consider untainted in that respect. These gestures and particulars become enhanced by their relationship with the larger cultural histories that they are embedded within.

ES: Right, that makes sense. I also notice that many of your materials are “readymades”, or lightly manipulated found objects which are abstracted from their originally intended use and presented in a new vista. This opens up the objects to represent their nostalgic evocations—a “return-to-myth”—and I am wondering if this misregistration can constitute “misuse” (or sabotage). To know something so well that one can deploy its fictions and reveal its contradictions from the start…

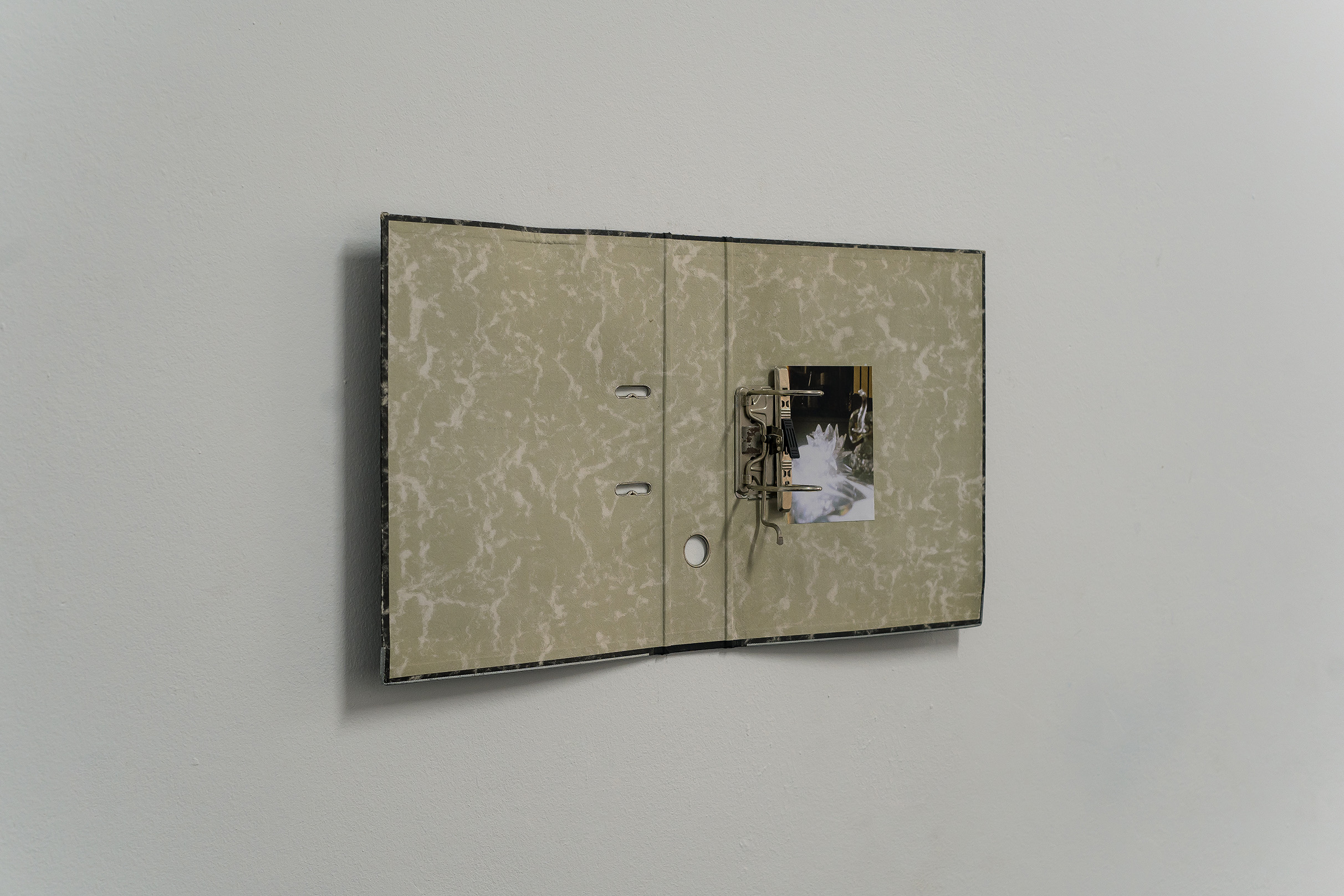

MX: I’ve always collected and archived objects, materials, and pictures—like modded cars, custom made obsessions, and face painted portraits—but only recently incorporated them into my practice. When I started, I was mostly using objects I wanted to reframe– ones that I thought had lost prevalence or meaning in the years since they’d been made or widely known, shedding their symbolic value in the process. With Class Memorial Bed (2021) and Class Memorial (2020) before it, I wanted to touch on the shifting values of middle-class desire. For their construction, I used found extruded aluminum from window sills and gates, where the aluminum goes through oxidation that turns it silver or gold, signaling an aspiration for the American dream– middle-class housing with three small bedrooms, ideal nuclear family, a kind of faux modernity.

ES: It sounds like a testament to your investment in eking out material culture and its ordinances—that you would find these refashioned and reanimated dinos, intended for some municipal purpose and, presumably, affective register, worn by time and a lack of investment.

MX: Digital avatars have become essentially omnipresent in our daily lives now– from profile pics to characters we use in video games, we’re constantly oscillating between virtual and physical space, fracturing our sense of self. It gives us the chance to reimagine ourselves, play around with our identity in ways we couldn’t in the physical world. The anonymity of the early internet intensified these possibilities. With forums and games like Second Life, people used to hide completely behind their avatar, using it as a mask, disassociating as much as possible. But since social media became big, there’s been a shift to something more physically representational; it’s become more like extended self-portraiture. With Twice Upon a While (2018 – ongoing), I wanted to explore a space somewhere in between the two. When I first created the work, I’d been pastiching analogue images into landscapes and platforms, kind of like theatrical stages to put imagined memories in, and was thinking of ways to further sublimate myself and the audience into these settings. I wanted to make an animation/video-game about a boy and a girl that burned down a church by mistake. As I was rendering the characters on Blender, I drafted monologues out of borrowed poetry books or translated folklore songs, and wrote a small scenario about one character continuously failing to complete its tasks in the way it was expected to, eventually leading to a sort of breakdown (drawing parallels between the character and my younger self). I was sketching this out at an age just before puberty, when you’re still sort of unsure about how the world works, kind of naive and innocent. Eventually, it became a sort of symbol, or maybe an icon, for that state of suspension in a time before understanding– looping it back into the liminal.

ES: And your work is indeed tracing and excavating those choreographies. Thank you for taking the time to do so with me!

Marina Xenofontos is a sculptor working through painting, installation, video, and animation. Acutely aware of the rifts produced in a personal memory when confronted with the hegemonic, ideologically produced versions of history, her work narrates a struggle to recoup the imaginary, lost in the dissonance between them. Affected by the politics of intersubjectivity, the dichotomies of individuality and collectivity, proximity and distance, her practice morphs their contradictions into a preoccupation with the personal in contrast to the political. Excavating everyday relics – symbols of lost futures and minor histories – she collides them with the hypermodern; playing-up and repeating the failures produced through their frictions. Hues and rainbows, deja-vu and avatars, sci-fi and fairy tales, all alike are brought into orbit—becoming points of contention for the mechanisms of production and understanding of subjectivity and history.