Although they seldom exhibit together, Monia Ben Hamouda and Michele Gabriele represent a rare genre of artist-duo whose separate sensibilities enhance their in-situ collaboration. For Gabriele, sculpture is the application of strategic fiction, or what he calls “post-digital hyper materialism.” His work takes the form of ready-made, sculptural assemblage: from velociraptor heads that seem torn from an animatronic specimen to newer work featuring animated, anthropomorphized, and intricately woven branches. Ben Hamouda takes a personal-poetic approach articulated through cultural and religious symbologies examined within a Muslim cultural habitus. In work situated between figuration and abstraction, Ben Hamouda fuses high-tech processes with calligraphic precision to explore aniconism. Both artists’ practices apply pressure to ready-mades and representation but toward different ends: Gabriele’s post-human, post-technologic approach to the grotesque and its animacies commingle with Ben Hamouda’s complex play of art, culture, language, and religion. The product is a rich set of gestural exorcisms of tradition in a politicized present.

—Elizaveta Shneyderman

Elizaveta Shneyderman

For both of you this is your first time in the United States. It comes at a strange time in the world. Has your visit here so far provided any surprises or insights?

Monia Ben Hamouda

We feel very lucky to be here. We’ve seen some amazing places and met some incredible artists and thinkers. The system of art here is so interesting and prolific, and everybody is so professional. But we’ve also had to confront parts of the US we don’t hear about as much. We see that the country is experiencing serious internal conflicts despite its status as a leader in democracy.

Michele Gabriele

It’s a strange time for the world, it’s true. But it’s also been an extremely psychologically complex time for me, so lately I’ve had to sort of forget about the world and this contemporary moment that demands all your attention in one instant only to be replaced with something else in the next, and spend most of my days trying to stay focused on work and remain positive about everything that concerns my present and my future in the hopes of being able to get a better grip on reality.

We arrived in New York City, and evidently something was wrong with my body language or my luggage, so they put me in a room for further checks with the police. Lots of questions. It was very unsettling.

In Holyoke everything is rust-colored, which was my favorite color when I was growing up. It’s very beautiful. Being surrounded by this color night and day must have some healing power; since I’ve been here, I’ve noticed both my body and my mind are experiencing less stress.

ES

Over the past few years, you’ve both become increasingly busy. Currently you’re here working on two projects simultaneously: a residence at lower_cavity in semi-rural Massachusetts and a gallery exhibition at ASHES/ASHES in New York City. The latter is a more traditional white-cube environment; the former is a huge, semi-subterranean industrial space. How are you approaching these two projects in terms of responding to the different contexts? More generally, how do you develop projects, especially when dealing with the demands of working under multiple deadlines?

MBH

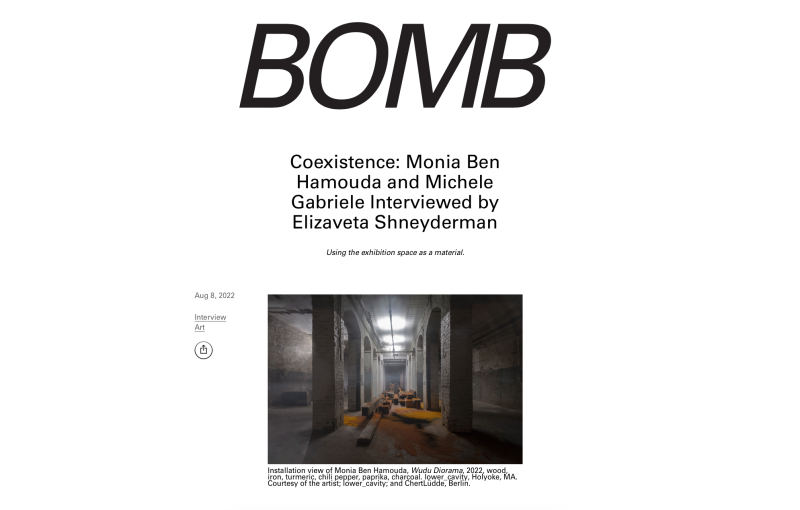

We both work very well under pressure. It’s always a challenge for me to work on several projects at the same time, but it also gives me the opportunity to explore a subject in different ways at once rather than have things be divided from each other. Often this means that the projects are very interconnected; they talk to each other and try to delve into different aspects of the same set of ideas. For example, during the residency, I worked on the idea of the deconstruction and reconstruction of representation and how these are linked to political events and cultural heritages. Since the space at lower_cavity has a very strong presence, I worked on a new, very large-scale installation that articulates the links between architecture and physical and spiritual protection, imagery, and religious spaces. I’m using the project to question how destroyed architecture and political events are connected and what roles architectural elements play in cult beliefs, migration processes, and art history.

The two metal sculptures on display at ASHES/ASHES in New York are part of my series Aniconism as Figuration Urgency (2021–ongoing) which explores the denial of representation of human beings, animals, and icons in Muslim culture. The sculptures are based on calligraphic writing and reflect on cultural fractures, identity, and the confrontation between tradition and personal expression.

MG

For me, every project is different. It’s rare for me to have difficulty with multiple deadlines. My mother has always said that even as a child I worked well under pressure! During this residency, I tried to understand the unique features of the context I found myself in. I treated this context as a kind of source material, almost like a physical material, and I asked myself how my work and research would look if it had been developed in this environment. I tried to respond and adapt to the spaces around me; it’s like trying to listen to the story that the space was already telling itself before my arrival and then finding a way to insert myself and my own narrative.

As a starting point for this process, I worked with an image I had been carrying around in my head recently: a young person wanders around an art museum with a sheet of paper in their hand, shyly copying the work on the walls, head bowed to one side. They sit in the center of the gallery in full view of everyone but at the same time hiding from everyone, resenting the stares. This mental image brought a flood of discordant emotions for me, such as the gulf between the student and the artworks around them, the embarrassment created by the awareness of this distance, the sense of need and of inadequacy. Refracting these images and feelings through the lens of the new environment in which I found myself became the basis for the works I produced.

ES

You work very closely together and often alongside each other but never necessarily in direct collaboration. Can you talk a bit about the ways your practices and working processes inform and resonate with each other?

MBH

We share studio space, so the fact that our works are generated in the same physical space is part of it; but mainly I think it’s that our initial ideas and questions for our work all find their origins in our conversations with each other. So these ideas naturally stay together and confront each other, and this is strangely something that is very visible from the outside as well. It’s not unusual that we get invitations for the same shows. I don’t think anyone knows my work as well as Michele does.

MG

We are continually working and so talk a lot about work and about art in general. We collaborate in life; and this life crashes daily onto our art, like a wave that keeps crashing on the beach, inexorably.

ES

Both of you have been showing extensively throughout Europe, although each of you has developed different kinds of followings. As both partners and artists continually working alongside each other, what kind of strategies have you developed for navigating the demands of traveling and exhibiting while developing new work?

MBH

Yes, lately the demand for both of our work has really increased. We try to spend as much time as possible in the studio, and we often help each other a lot. Michele often accompanies me on installations, and I do the same for him. It’s our little pact, though it’s becoming increasingly clear that we will soon have to hire one or more assistants. But I like to think about ourselves as a team, even if we have two different careers and practices. It’s very important to have allies in art.

ES

While the specific issues and content in your work are very different, both of your practices have a strong, almost visceral sense of materiality. There also seems to be a shared interest in a kind of visual complexity that teases the eye with a sense of familiar associations that never quite resolve. What sort of shared affinities do you find in each other’s work?

MBH

I believe that our respective research is formally separate, but the long-term goal is the same: to explore contemporaneity and develop a language related to it. We have in common many things: an urgent, almost violent dialogue with the viewer; the use of the exhibition space as a material and not just as a container for the work; and certain formal affinities and obsessions. But above all we are both very attached to a vision of our work as being linked to art history. I think that Michele’s work is related to European and Renaissance art, to painting, to Vedutismo, and also to scenography. And in a way, I see my work as a contemporary response to the questions posed in ancient North African and Islamic art, to the traditions and influences of my heritage.

MG

There is a force that tends toward chaos or disorder; everything in the universe is subject to this. Even as we do this interview, we are undergoing a process of decay, slowly coming together in this process in which everything will eventually be reduced to an evenly distributed state. I find in this tendency toward disorder a very spiritual and poetic principle. We can see it in the countless colors of grains of sand that together appear as one color. I am inspired by these concepts in my work, and from them I try to learn that sense of freedom that allows me to use elements belonging to different worlds and imaginaries and make them coexist within the same work.

There are many aspects that Monia and I have in common and many others that make us very different. Lately, what I love most is our relationship with this phenomenon that regulates the world and slowly is bringing everything together.